So it was the long Thanksgiving weekend and the steady stream of horrifying news about police brutality at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests in North Dakota made the Standing Rock reservation sound like a dandy place to spend the holiday and give thanks for being European-American.

I decided that a fun way to pass the seven-hour drive to Standing Rock would be to listen to Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, an audiobook about what happened to the Native Americans as European immigrants expanded westward throughout the 1800s. I figured this would in no way be soul-shatteringly depressing and disillusioning.

Spoiler alert, don’t read that book if you want to keep on believing that North America was an empty wilderness that we tamed through our sheer awesomeness and fair-minded dealings. Or that maybe some sketchy stuff went down, but it was a sadly inevitable clash of cultures, and we definitely didn’t systematically exterminate millions of people just for being inconvenient.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone!

This audio death-march through the history of the American West was punctuated by a continual stream of police cars flying by me on the highway with their lights flashing. After a while this became bewildering, because North Dakota has like twelve people and two cops. One to make sure nobody’s driving a tractor too slow on the freeway and the other to investigate reports of black people in the area. I’m kidding! There are 7,000 black people in the entire state of North Dakota.

As the police cars streamed by, it quickly became clear that every last cop in North Dakota was headed in the same direction. As well as half the cops from the surrounding states. As I got closer and closer to Standing Rock, it became more obvious that we were all headed to the same place. Fun!

Driving through endless abortion billboard nothing, I thought about how this trip had come about. My mom’s a therapist on a reservation in Northern California, and she hatched the Standing Rock plan upon hearing client after client talk about what a life-changing experience their time at Standing Rock had been. Surely we could go and volunteer, donate food and clothes, pray with everyone, and give our support?

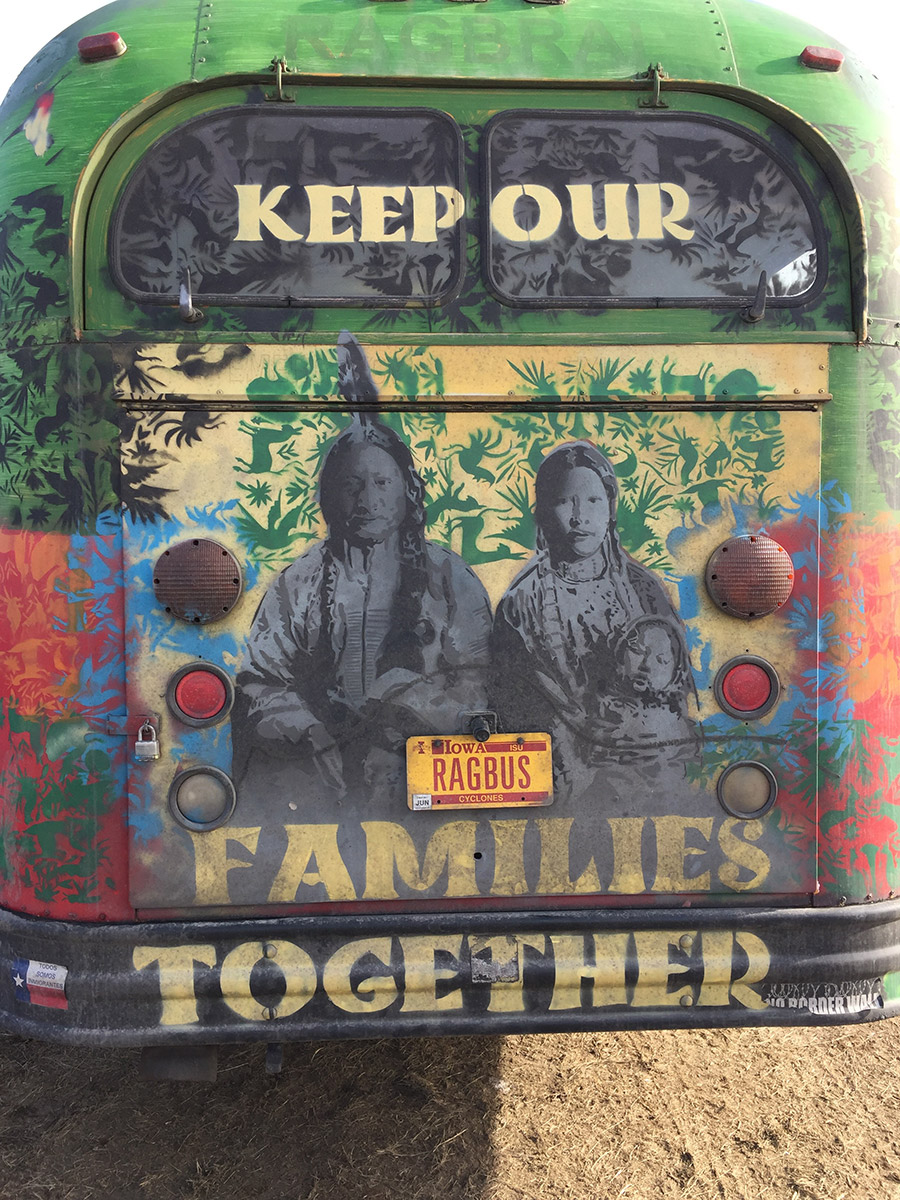

I honestly didn’t know that much about it, so I started to read. Anyone who knows me knows I’m a research junkie, and whether I’m going to clash with militarily-armed police or buy a pair of socks, I read everything there is to read. According to news articles, there were about 1,000 people camping at Standing Rock. And these rowdy rascals were occasionally clashing with the police and chaining themselves to equipment on the drill pad to prevent Energy Transfer Partners from drilling under the Missouri River, because the tribe kind of needs that water to survive, and these kind of pipelines leak oil all the freaking time. The pipeline had previously been planned to pass by the city of Bismarck, until somebody realized a bunch of white people live there.

Sure, the pipeline company had hired private security contractors that had turned attack dogs loose on protesters, but whattaya gonna do? These protesters were violent turds and most of them weren’t even white.

I generally try to give everyone the benefit of the doubt, including the police. My mom was a cop for many years and worked on the rough side of the city, so I know something about what it’s like to have a loved one get shot at for a living. So I came into the whole thing figuring the protesters had a point, but that they were probably getting carried away, leading law enforcement to inevitably respond in kind.

Then came the protest on November 20th, when all hell broke loose and the police opened up on a large group of protesters with concussion grenades, rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannons. It was 20 degrees out, which makes drenching people with cold water (especially people who are nowhere near real shelter) something between a real dick move and aggravated assault.

The police released a statement claiming they’d only turned the hoses on to put out brush fires started by the rioting protesters, and that they never, ever used rubber bullets or concussion grenades. They don’t even carry such outrageous things! About four seconds later, video was posted on social media showing the police spraying the hoses right into the crowd for something like nine hours straight. The brushfires? Started by hot tear gas canisters shot by police that landed in the dry brush. Hmmmm.

Then it came out that a girl at the protest who was carrying water to the front lines had been hit by one of the concussion grenades, which completely blew her arm apart. Don’t Google that picture, trust me. Other people from the camp came forward with stories of their traumatic encounters with concussion grenades the police supposedly weren’t using. Others showed off their welts from the rubber bullets that weren’t fired.

The police released another statement claiming the girl who was hurt had been trying to blow up a police vehicle with a pipe bomb, when it went off. Oh, you knucklehead millennials! Can’t you do anything right?

The more I read and compared the stories in the major media with what the people involved were posting on social media and blogs, it became clear the media was pretty much just asking the police what happened and reporting whatever they said as fact. This makes for an easy read for most audiences, since mainstream America trusts the police a lot more than they trust a bunch of dirty Indians and spoiled millennials who were probably just there to take selfies. Yuck, millennials, am I right?

I hate to sound naïve but I have to admit I found this pretty disillusioning. Weren’t there any reporters doing any kind of investigative journalism? Or, like, their jobs? At the most basic level? I wondered how many news articles I had read and accepted over the years that were complete lazy bullshit.

What did I spend most of my research time on? Understanding the legal issues behind the pipeline build. That took some doing. Most people just ask who owns the land the pipeline is being built on, and when they hear it’s not the tribe, their sympathy abruptly ends. “Sorry Indians, it’s not your land and I’ve got fantasy football to catch up on!” It’s not quite that simple, however, in that it is the tribe’s land, according to a treaty the US government broke, twice, once it was no longer convenient for them to honor it. Even leaving that issue aside, the pipeline build is in violation of both environmental impact laws (the tribe’s water access rights) and historical preservation laws (the tribe’s burial grounds that the pipeline cuts through) regardless of who owns the land. Again, we’re just ignoring those laws now because they’re inconvenient for us.

My co-workers had heard about the concussion grenades and the rubber bullets and the attack dogs, so they were pretty well convinced that I was headed off to die for Thanksgiving. North Dakota yokel cops armed with Patriot Act military toys they had no idea how to use was a scary prospect indeed. I reassured everyone that I wasn’t going there to clash with the police, I just wanted to volunteer at camp and pray with the tribe for their success. I couldn’t vouch for my brother Aster, since he has no fear and was probably going to dive headfirst into the protesting, but at least my mom had worked out a system where no more than two of us would go to a protest at a time, so the third could bail the other two out of jail if necessary. So none of my co-workers had to worry about getting a call in the middle of the night to drive to North Dakota and bail me out of jail. Probably.

Meanwhile, I was doing research on how to keep from getting fucked up by tear gas. Just in case. Like I said, I research everything. I had my Amazon cart full of the right kind of airtight swim goggles and a respirator that was the right filter grade for tear gas, wondering if I’d regret spending all this money for a clash I wasn’t planning on having. At the last minute I decided I didn’t need all that stuff.

The Wednesday before Thanksgiving, I got a text from my brother. I figured he and my mom were driving somewhere across Montana at that point, on their way over from California. I was timing my departure from Minneapolis to meet them at the reservation on Wednesday night. Where you guys at?

Oregon. Whaaaaaaat? There was snow and mom lost her cell phone at a gas station and we took a nap. I thought about the food slowly going bad in the back of my fully-loaded car, sitting in the parking lot at work.

I re-scheduled my departure for the next morning, since Aster had the tent and I really didn’t want to sleep in my car in a freezing cold field in North Dakota that night. I went home to sleep, then got out on the road at 4am with all the truckers hopped up on NoDoz and regular people steeling themselves for some truly unpleasant Thanksgiving family time. And, eventually, all the cops in the entire world.

Drawing near to my destination, I had to detour and take the long way around to the camp, because the police had barricaded highway 1806 to keep protesters away from the drill pad and to make it a pain in the ass for anyone to get to the camp. The long way around actually had a beautiful Martian landscape quality to it, expansive ranches and buttes, a lot more interesting than the rest of the pancake-flat drive from Minneapolis. I was looking for Oceti Sakowin, the front-line camp where all the action was. I knew I was close when I started having to swerve around all manner of strange people wandering around on the highway. I passed Sacred Stone, the original protest camp, and Red Warrior, the angry young camp where they rage against the machine and pierce things, probably. Then, finally, I reached Oceti Sakowin.

Holy shit. Remember the news reports about how there were about 1,000 people in total across all three camps? Oceti Sakowin was immense, like a city of tents and teepees. I’d love to share a picture of the whole thing but I couldn’t get far enough away to fit the whole thing in one photo. There had to be 10,000 people in this camp alone.

I joined the long line of cars entering the camp and drove through the camp city in a daze, partially trying to find an empty space where we could set up a tent and partially just gawking at the Lollapallooza all around me. Hordes of people, tents, teepees, huge mess hall tents, is that a geodesic dome? I drove through the entire camp, not seeing any tent-sized empty spaces, and before I knew it I was following a line of cars headed out the back side of the camp. Where are we even going? About a mile ahead there was a huge congregation of people. What the hell, let’s see what they’re up to. Maybe we can camp over there.

Before long my car was surrounded by people walking to whatever the hell we were heading toward. By the way, the Prius is a terrible car to drive through a crowd, being as it is utterly silent at low speeds. I rolled down my window so I could say sorry repeatedly. Cars were pulling off and parking haphazardly in the tall, dead grass. Suddenly somebody wearing a name badge was asking if I was a medic and then yelling at me for being on the road without being a medic. I pulled over into the tall, dead grass and hoped nothing would catch on fire beneath my car. I got out and followed the throng of people to wherever they were thronging.

Hundreds of people were crowded onto a beach at the end of a trail, chanting and waving signs. Across the river there stood a large hill. I soon learned that this was Turtle Island, and that hill was a sacred burial ground for the Sioux. Standing at the top of the hill were all the cops that had passed me on my drive to North Dakota. A line of police officers in riot gear yelled down at the crowd with a megaphone. From the top of the tribe’s sacred burial hill. Nice move, dicks.

Everyone at ground level was trying to get across the river to join a prayer circle on the beach at the base of the hill. Some were crossing a rickety, impromptu plywood bridge that spanned from beach to beach. Others were kayaking across.

The police megaphoned down for everyone to get off the beach. People yelled for the police to get off their ancestors’ graves. More police showed up to join the show of dominance from the top of the hill.

That was all this whole thing was about, the cops scrambling from three states to stop people from praying for their ancestors and for the water and for the police to get the fuck off their graves. The police sprayed a hose down at the prayer circle.

I worked my way to the water’s edge. On the beach, across the river, one member of the tribe started a small campfire on the sand, then fanned the smoke from the fire up toward the cops standing at the crest of the hill. The crowd erupted in a cheer.

The emotion of the crowd was absolutely overwhelming, I felt like I was going to pass out. I may have cried. I definitely cried. Tribe members on the other side of the river waved their banners and entreated the rest of us to cross the river and join them.

“Come on! Are you just here for a selfie? Come pray with us!”

Shit yeah I want to do that. I looked up at the heavily armed police spraying their hose, then around at the millennial protest tourists all around me. They were all wearing goggles, respirators, gas masks, helmets. One dude had a bullet-proof vest on. Holy shit. I quickly jogged back to my car and grabbed the shitty construction goggles I’d brought from home just in case, and my rain coat, and headed back to the river’s edge.

It took a while to work my way through the crowd to the plywood bridge, then the second I got there they closed the bridge on our side so people on the opposite side who didn’t want to get tear gassed or sent to Guantanamo could cross back over. This took about half an hour. Then they let two people from my side across. I was next in line when they closed the footbridge so the prayer circle could begin.

Goddammmit. “You can pray just as well from over here,” said a tribal member standing next to me. Good point, wise dude. Now I felt like a wank for trying so hard to get across the bridge. I gradually sank into the foot-deep mud at the river’s edge as we prayed for our ancestors and the Earth in the four cardinal directions. A hippie-looking dude fell into the deep mud in front of me. I reached out and picked him back up. Holy togetherness!

Later I discovered that the actress Shailene Woodley was standing somewhere behind me during all of this, taking a selfie.

I stayed for a few hours, joining prayers and chants when I could, and wandering through the crowd to get a feel for everyone who was there. “Mni Wiconi!” Water is life. Who could be against this? Assholes. Could there really be that many assholes?

The emotion of the entire scene was constantly heightened by not knowing if the police would suddenly start tear gassing everyone. Eventually it became clear that there were too many cameras, too many people, too much attention on Thanksgiving day. The police seemed content with mere intimidation, and eventually the fact that I hadn’t eaten all day hit me like a punch in the stomach. I decided to head back to the main camp to see if my mom and Aster had arrived yet.

As I walked along the path back to camp, the majority of the traffic was people still walking toward the protest.

I felt a bit like I was floating, filled with goodwill from the energy of the crowd and the experience of bonding with hundreds of people over something positive. Whenever I’m passing through a large group of people, in an airport or at a major environmental protest action, I always like to do a little prayer where I look each person I pass in the eyes, picture them full of joy, and silently wish for their enlightenment. I was practicing this, walking along the dirt path as it curved along the river, my hands folded in my coat pockets, hidden away from the cold. My mind wandered for a moment and I was suddenly inside the memory of walking along a similar path, wearing a monk’s robes and holding a string of prayer beads in one hand, counting off the blessings I was saying for each person I passed on the trail. The cold sun shone down and suddenly I was back in North Dakota in my muddy shoes. All right Standing Rock, have it your way. I take back all the jokes I’ve ever made about North Dakota, except the ones about racism and unrelenting flatness.

In time I met my mom and Aster on the path. Aster was impressed by my goggles, which I didn’t realize I was still wearing. We headed back into camp together and after some effort, found Aster’s friends Mani and Rosie who were there from the east coast. We set up our own camp nearby.

I think we were in camp less than an hour when the kids found me. I have this thing where little kids love me. I’m not sure why. I don’t have kids of my own or any plans for any. I like kids, but I also like honey badgers, and I’m not bringing one of those things home with me either. Anyway, the couple from Minneapolis in the next tent over had three little Native kids, two little girls and a boy, aged from about 2 to 5. The kids came over while I was unloading my car and followed me around the rest of the time we were at Standing Rock.

“You have pretty eyelashes.” Thanks, strange little girl. “This is my dolly, she is naked.” She sure is. “I like your hat!” Thank you. “You’re a girly man.” Yes. Yes I am.

All three of the kids piled into the back seat of my car uninvited so they could get a better look at me unloading all my gear. I was slightly concerned their parents would think I was kidnapping the kids, but they were either unconcerned by this or saw clearly that it was the other way around.

Everyone was hungry and I’d brought cutting edge veggie burgers from home, so before long I was manning a propane grill on Mani’s tailgate while the two little girls hung off my legs and the little boy tried to put his hands in the fire.

“Cheese! Can I have some of that cheese?” It’s vegan cheese so I’m not sure if you’re going to like- never mind you’re already eating it. “I don’t like this cheese.” That’s fine, just- yeah, just putting it on the dirty tailgate is fine. “I’m going to eat my sister’s cheese.” It’s been on the dirty- never mind. Is your mom okay with this? Where is your mom? “Watch while I make a dead grass angel!” I’m manning two propane grills at once that are precariously perched on a pickup truck tailgate while your brother continually tries to set himself on fire, so yes, I definitely have time to watch you lie down and make a dead grass angel. “I farted.”

After the sun went down it went from North Dakota in winter cold to damp, wet, soaks into your bones Oh My God cold. We quickly and necessarily made friends with the couple from Wisconsin on the other side of us who had started a campfire. It was lucky for us that they were awesome because we would have hung out with them regardless to keep from dying.

All day, cars had been streaming into camp ceaselessly, and this continued long into the night. Word was that Jane Fonda was there somewhere, and had donated food to the camp for Thanksgiving dinner. Some dude from the Black Eyed Peas was there. There were probably other celebrities there but everybody looks the same when they’re dressed like Randy from A Christmas Story.

We stayed up late getting to know our camp neighbors around the fire. This would become a nightly routine the entire time we were at camp, both because our neighbors were great and because, seriously, this was the only way not to die. Between Minnesota and Alaska I’ve lived in very cold places for nearly 20 years, but I can’t stress enough that living in civilization in the winter time is an entirely different bargain than living in a tent in a field in the winter time. It gradually dawned on me that talking around the fire every night must have been a major part of tribal life going back to the dawn of man, because being more than two feet away from the fire sucks a lot.

In the morning I woke up with a shiver, wedged tightly into our “three person” tent with my mom and Aster. We were sleeping in a three-season tent, which should come with a warning label explaining that none of those seasons is winter in North Dakota. Seriously, don’t do this. I opened my eyes and saw nothing, then realized at some point during the night I’d pulled my winter hat all the way down over my entire head like Dumb Donald from the Fat Albert cartoons. Only my mouth was protruding, and from my mouth stretched a long, thick trail of ice across my sleeping bag from where my breath had frozen solid during the night.

My mom had stuffed hand warmers down her socks before we went to sleep, and as I tried to regain feeling in my feet I wished I had followed her example instead of laughing. Crammed into a five degree sleeping bag inside another five degree sleeping bag, I attempted to shift my position. Not happening. Outside our tent, one of the little kids asked somebody if I was awake yet.

I had packed several changes of undergarments for our days in camp, and that first morning I realized how ridiculous this was. There was no way in hell I was taking off anything I was wearing. I crawled out to my car, put even more clothes on, and the kids and I headed out to explore the camp.

Rather than allow this to blossom into a beautifully verbose 400-page chronological account of our camp experience, we’ll shift gears now into an impressionistic blur of the various events that stick out in my memory:

My favorite experience came on our second day in camp. My mom and Aster had brought a copious amount of food to donate to the camp, as well as blankets to help everyone through the long, cold winter. I had decided to donate most of my winter clothing to the camp, a decision I felt awesome about until I got back to Minnesota from California in January and realized I was going to die. I’d also brought sleeping bags and various other winter shwag to donate.

We headed over to the massive clothing donation area and dropped off the clothes, after a brief internal struggle I had with the desire to instead put all of those clothes on at the same time, including the sleeping bags. Aster talked for a while with a Native gent who had found a jacket he liked but was struggling with the fact that it had a beer company logo on it, as he was in recovery. After we got done with the clothes, we headed over to the kitchen tent to donate the food.

We walked in with our arms full of sacks of rice, a huge cooler and other goods, and as I walked through the dining room tent I nodded to an elderly Native couple who were dining at a table off to one side. On my way back from the kitchen another woman stopped me and pointed to the Native man at the table.

“He likes your shirt.”

“Oh, hey, that’s cool!”

“No, no. This is an elder of the tribe. He’s a very important man. You should offer him your shirt.”

“Oh! Of course!”

I turned to the man. “Would you like to have this shirt?”

He sort of hemmed and hawed quietly.

The woman sitting across from him said “He’s too shy to say it, but he REALLY likes that shirt.”

I took off the shirt, folded it, and handed it to him.

“I… I did not mean to take your shirt,” he said with a beautiful, quiet humility. His entire manner radiated peace and calm wisdom.

“I would like for you to have this,” I told him. “Please, take it.”

He took the shirt, then slowly shook my hand and thanked me.

“You got another one for granny?” the woman sitting across from him joked.

The elder and I talked for a minute, then I walked back out to the car and told my mom about what had happened inside.

“I have another one of those shirts!” she said, excited. “We should bring it back for her!”

We headed back to our camp, got the second shirt, and came back. I walked into the dining tent and handed the second shirt to the elder.

“Hello! This one is for your wife.”

“Oh. I’ll let you know when I find one,” he cracked.

Whoops, that lady wasn’t his wife! Oh well.

“Don’t worry, I’ll see that she gets it.”

He noticed that I was wearing a different Standing Rock shirt now, one that said “STAND WITH STRONG HEARTS.”

“I like that shirt,” he smiled at me.

He then proceeded to tell my mom and me a long story about why he wasn’t married. It was amazing. He talked about his responsibilities as a tribal elder, how he had to be available for his people and travel to do spiritual work around the reservation. And how, to be in a relationship, he’d need to find a woman who was strong enough inside herself to not feel jealousy about all that he needed to give to others. Who wouldn’t need everything he had to give for herself. Otherwise, the relationship would pull him away from his service to his tribal brothers and sisters, which he could not in good conscience do. He had yet to find such a woman.

That such a quiet and thoughtful man had opened up so deeply to us, giving this teaching about relationships and opening up about his most private concerns and feelings, frankly kind of floored me. I felt like he had seen something in us that told him we were worth opening up to, that we would understand and take value from what he told us. I felt very flattered and touched by this.

We talked with him for a bit longer, then one of my mom’s co-workers who had quit her job to come live at the camp full-time spotted her and we were pulled away.

A surprising number of people had done just this, dropping everything in their lives and coming to live at the camp. I think I understood what they felt. There was a special feeling at the camp, the feeling of banding together with people you loved over a shared cause, a worthy cause that you knew was right. Even the people like us who were just passing through, you could feel that after the madness of the election, people really wanted to push back and do something for the good of humanity.

The tribal members that I talked to said they’d never seen anything like this before. The whites had never been on their side like this before. I found that beautiful and very sad at the same time.

The time at camp passed very quickly, and most of our opportunities to volunteer came in the form of doing spiritual work, joining prayers, talking to people, etc. Mom and I stopped by the therapy tent to volunteer as counselors, and they gave my mom a patch to wear on her shoulder, letting people know they could come to her with their shit.

The only person who seemed to notice this was a woman who stopped us and who turned out to be writing a book with the author of An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, the book my mom happened to be reading on the drive out to Standing Rock. Yes, that’s an insane coincidence that really happened. The woman interviewed my mom for her new book and they talked about counseling people with historical trauma. Then my mom turned the tables and ended up counseling her, because of course.

The scariest and most disorienting aspect of being at the camp to me was climbing up the hill across the road from camp and seeing the police barricade on the highway 1806 bridge crossing the river. I feel strange typing “police,” as this was clearly a military-style installation. Roadblock would have been the wrong word for what this was. This was something airlifted in from Fallujah.

The bridge itself was covered in dozens of huge concrete barriers, each the size of a small car. Beyond those barriers were larger concrete barriers forming a wall, covered in razor wire. Beyond the wall were all the military Humvees, the armored vehicles, the huge water cannon truck, and more police cars than I could count. Is that a sniper? The tribe asked us not to get close enough to be able to tell if that was a sniper.

Sometime after we left, two surface-to-air missile systems were added to the barricade, pointed at the camp. This is the country we live in now? Who are these guys protecting and serving? Emails were leaked that appeared to show the police were being paid by the pipeline company.

A stray dog wandered toward the bridge.

“Somebody get that dog before the cops shoot it.”

I talked to a lot of people, trying to understand how any of this was acceptable. How do the people of North Dakota feel about their tax dollars paying for all this insanity? “They’re under the mistaken belief that the pipeline is going to bring them jobs. After the initial build, there will be about three maintenance jobs. Or they think it’s something something energy independence. But the whole point of the pipeline is to export oil to China.”

Don’t people here care that the tribe’s water supply is being endangered for something that brings them no benefit at all? “The whites in North Dakota HATE the Native Americans.” I really wish that part was untrue, but everything I saw supported this conclusion. It was pure cowboys and Indians. You didn’t want to drive up to Mandan and tell people you were staying at the camp. All of the Ace Hardware locations in North Dakota stopped selling propane tanks to anyone who looked like they might be from camp. You know, the tanks you need to cook food or run a heater to keep your kids alive. They explained this with some nonsense about improvised explosive devices before media attention shamed them into stopping.

On one of our last days in camp, we attended a direct action training. This was a class you were supposed to take before you took part in any kind of protest or clash with the police, like the one I had blundered into and joined 30 seconds after I got to camp. There were no more direct actions during the rest of our time there, but it was still a fascinating experience.

A large group of us sat on the grass while trainers explained to us what to do if you got tear gas in your eyes and what to do if you get arrested and how you should write the legal defense hotline number on your arm with a Sharpie now. They explained that there was a legal aid fund that would pay for bail for anyone arrested at one of the protests, which I thought was impressive.

Then they detailed the treatment we should expect from the police. I’d heard a bit about this before the trip from various blogs and posts, about the police strip-searching protesters and then leaving them naked and wet in cold cells for extended periods of time, locking them in dog kennels, etc. Just the normal public service kind of stuff our tax dollars are intended for. The trainers congratulated those of us who were white, since the worst treatment was reserved for the tribal members when they were arrested.

One detail struck me as amazingly petty. Most tribe members carry some kind of medicine, a pouch of herbs or a special stone that is spiritually significant to them. The police love confiscating these, and refusing to give them back upon a protester’s release. Over time, the tribe had formally pressed for the police to return these items. Finally, the police relented and returned the items. They had peed on all of them.

The trainers also ran us through various drills on how to march as a group and how to lock arms with the people near us to make ourselves hard to arrest and carry away. Marching around a field, arms locked with strangers while we chanted together, felt both a little silly and a little wonderful at the same time.

The day after our prayer circle protest at the beach, we went back and the police had covered the entire Turtle Island beach in razor wire, to keep the world safe from any more prayer services. For good measure, they’d also crossed the river, taken all the kayaks and canoes on the other side, and poked holes in all of them.

Is this somehow the job of the police? Isn’t that private property? I don’t understand any of this.

I’d spent the entire drive to Standing Rock in a stake of shock, learning the particulars of how we’d treated the Native Americans as the new nation of America expanded west. I know that sounds naïve, like who doesn’t know that bad shit went down, but hearing all of the particulars is something different. At least it was for me. As shattered as this left me feeling, I guess I took some comfort in thinking at least we weren’t doing that kind of thing now. Every day at camp I became less and less sure of this.

One thing that didn’t help any incipient paranoia was that there was a small plane low in the air, circling the camp, 24/7. All day, all night. Loop, loop, loop. People told stories of how it was a surveillance plane that was capturing all the cell phone traffic from the camp, monitoring calls and texts. This might sound kind of insane, but it’s exactly the kind of thing police do in high drug trafficking areas in cities all over the country, so it wasn’t exactly far-fetched. The US Marshals service and FBI do the same thing. Several people told me their cell phones had gone inexplicably dead after arriving at camp, in spite of starting out fully charged. I supposed a fake tower could keep your phone perpetually searching for signal and drain the battery pretty fast.

If it wasn’t some form of surveillance, what was it? How could a private pilot even afford to fly all day and all night like that? Why would they?

Jesus Christ, where do we live again?

The great irony of all of this was that the camp was one of the most peaceful, prayerful places I’ve ever been to. Based on the news I’d expected it to be like some kind of militant Burning Man festival, but it was nothing like that. We were inundated with constant reminders to not antagonize the police, don’t give them any excuse to hurt people. Respect the tribe and the peace of the camp. I was continually and deeply impressed by the reverence the tribe held for the peaceful energy of the land.

The camp itself was constant singing, dancing and prayers. The contrast between the beauty of the camp and the ugliness of the police force surrounding it was bewildering.

Wandering through camp, you’d be walking through a crowd when suddenly everyone would start singing:

“Come on people rise with the water, all colors, all creeds, hear the voice of my great granddaughter, singing Mni Wiconi…”

I’d never understood before that Native American songs and dances are all prayers. The drums are to clear away old energy. The sage smoke carries away negative spirits. At the perpetual ceremonial campfire at the center of camp, Natives from different tribes would take turns at the microphone late into the night, singing their tribe’s holy songs. We’d fall asleep to these songs echoing across the fields each night.

Where was the anger about what was happening? The only anger I saw was when the Red Warrior Camp came over on our last night there and set up a rap concert out in an open field. This was clearly an opportunity for the young people of the tribe to blow off steam. It was quite a strange juxtaposition, sitting in this peaceful spiritual camp, talking around the campfire, as heavy beats and angry words boomed across the valley. They were clearly raging against the machine over there. We laughed as we attempted to decipher the lyrics.

“Fuckin’fuckin’fuckin’fuckin’fuckin’fuckin’biiiiiiiiitch!”

“I think there was one more fuckin’ in there.”

I was really surprised that the elders were okay with this, given everything I’d observed so far. But there also seemed to be an element of letting the young people have their own experience and make their own choices. Still, I wondered how the tribal elders would feel about this heavy energy of anger saturating the peaceful land they loved so much.

After the concert ended, we laid in the tent talking for quite a while. After an hour or two, I started to hear tribal singing in the distance. Then drums. The tribe members had waited for the Red Warrior group to all go home, then they’d walked out to the field to sing and dance and clear away all that angry energy. They sang and danced and drummed in that field all through the night, into the early morning hours.

I’m still impressed when I think about this.

That night as we were talking in the tent, my mom told me about the bear dance. This is a ceremony where a few special members of the tribe will fast for days to prepare themselves, then at a ceremonial gathering, they dance dressed as bears. Spiritually, they become bears and are no longer men. Then they go to each member of the tribe who is sick. Physically, mentally or spiritually sick. They will look this person deeply in the eyes and take their illness away from them, taking it into themselves. The bear dancer then goes off and throws up, purging out all the negative energy or spirits they have taken away from that person.

I was deeply, deeply fascinated in hearing about this practice. It really touched a nerve in me and I wanted to know everything about it.

The next day we went our separate ways and went home, and by the time I got home I was horribly sick. I rarely ever get sick but this time I missed a whole week of work and spent it in a fevered delirium, tossing and turning in vivid Native American-themed dreams. I had one dream where the world filled up with wolves, so many wolves I was drowning in them and I could feel myself dying, until I fought myself awake and woke up choking. Others were too abstract to even adequately describe, vivid geometric shapes in Native American designs swirling before me.

Eventually I recovered enough to rejoin the world, though I wouldn’t recover fully until participating in a sweat ceremony on the reservation in California a month later. What was this? I’d never been sick like this before. The doctor said it wasn’t strep throat. He didn’t know what it was. It was stranger than anything I’d ever had before.

One night I was meditating and I suddenly saw very clearly that when my mom told me about the bear dance, she was telling me what we were doing at Standing Rock. We didn’t know it consciously at the time, but we were carrying away some of the historical trauma that had been burdening the tribe for generations, to take it home and purge it out. Holy shit. I did bear medicine.

A short time later the Army Corps of Engineers blocked the pipeline corporation’s access to drill under the river, pending further environmental review. Was this victory? Would Trump screw this up? Impossible to know, but I knew the trip had changed me, and I hoped our support had helped the people and their cause in some way.

If this saga continues on, I could see myself returning to the camp one day.

But this time I’m bringing a four season tent.