After you’ve spent a few days in the country with the second-highest murder rate in the world, where is there to go? To the country with the highest murder rate? I like the way you think!

Welcome to El Salvador.

Driving around El Salvador, the disconnect was startling. This is it? This is the place everyone is so afraid to go to? Sunny, beautiful, green, and full of some of the sweetest people I’ve met anywhere, El Salvador was almost comically serene. I felt safer there than I have in most of the other countries I’ve visited, and safer than I feel in just about any big city in the US. I loved it there.

Clearly, the murder rate is real, and El Salvador’s gang problem is real, but being there was nothing like what I expected. From everything I could tell, being in a gang in El Salvador is extremely dangerous and the high murder rate is almost entirely the result of all the gang members shooting each other over gang business. But just being a person there didn’t feel sketchy at all to me. And I was staying in San Salvador, which is gang central and the place every online guide says “Good God, for the love of Christ don’t go to San Salvador!!”

I’ve come to be deeply fascinated by the perception of danger. It’s been my experience that Americans simultaneously view America as safer than it actually is and also view the rest of the world as far more dangerous than it really is. This is a really fascinating phenomena, because it seems to come down to both psychology and propaganda.

I think there’s a very human response where we become numb to whatever the particular danger is wherever we live, and come to think of it not really as “danger,” but just the way life is. We shrug off the huge number of firearm murders in the US because, well, I mean, if people have guns they’re gonna shoot each other sometimes, right? Whatchagonna do? That’s life. This seems so self-evident that I didn’t even really see this bias myself until I heard about people in ultra-safe Japan who described how terrified they had been while visiting the US.

My reaction to them was oh, it’s fine, you’re just watching too many sensationalized news accounts about the United States. But is it fine? Or have I just adapted, rationalized and normalized the not-fineness of where I live? I literally felt like I could have slept on the street with my wallet open in Japan and come out of it okay. Granted that’s one end of the scale, but it’s not out there by itself. And it recalibrates your entire scale when you realize what’s possible in such a highly-populated, heavily urban country. Before I really started traveling I assumed everywhere was like the US, or worse. It’s not.

These Japanese tourists actually did see someone get beat down in the street while they were in the US. I had a friend visit New York from Australia, and immediately after I reassured him about the safety of New York, somebody was shot dead in front of the Empire State Building while he was inside. Just because we’re numb to these things doesn’t mean they’re not happening or “don’t count” when assessing the safety of our own country. I think we all badly want to believe we live somewhere safe, and we all tend to bend reality until we can believe it.

I think there’s also an element of propaganda at play. Every country wants their people to feel glad they live there, and one of the ways to accomplish this is to make other places sound worse. Americans are raised to believe America is idyllic and ultra-safe, but watch your ass should you ever cross into Mexico. Man, that place is a zoo! Be glad you don’t live down there! Never mind that we’re Canada’s Mexico. And Central America is Mexico’s Mexico. Every place has an “other” that they project all their fears onto.

As you travel south, this perception does a weird flip where Central Americans seem worried about going to Colombia, but then I’ve been told Colombians flip the script and say they’d never go to Central America. So somewhere around the Panama Canal everything flips upside-down and the bad shit’s north of you now.

I don’t mean to suggest the US is the most dangerous place in the world, I’ve just found it to be closer to the middle than I think most Americans believe.

This trip posed a logistical challenge in terms of how in the hell I was going to get my white ass from Honduras to El Salvador. Copan is a major Mayan archaeological site, but not exactly a major metropolis. The only way to fly to San Salvador would have been to take a bus all the way back across Honduras to San Pedro Sula on the far opposite side of the country first, and I didn’t have time for that shit. And rental car companies are weird about letting you rent one of their cars and then return it two countries over. None of the safer tourist-class buses go to El Salvador from Copan. You can take the chicken buses the locals use, but that would involve a long and complicated series of transfers overly dependent on my mierda Spanish, and this would definitely be the weak spot in my overall plan to not get robbed or killed in Honduras.

There were rumors of shuttles that ran between Copan and San Salvador, but they were said to only run a few times a week and there wasn’t any information online about which days they actually ran. The advice was basically to ask at your hotel. Which is a real bitch to plan a trip around, since I was booking hotels in two different countries based on when the shuttle ran but wouldn’t know the shuttle schedule until I had a hotel booked. I ended up booking rooms for the same night in both Honduras and El Salvador, so I’d have somewhere to sleep no matter how the shuttle madness shook out.

The “shuttle” turned out to be the receptionist at my tiny hotel calling her cousin, who drove me through Guatemala to El Salvador in the middle of the night. Good enough, Honduras!

As we pulled up to the Guatemalan border, I suddenly remembered this was supposed to be a madhouse because of the thousands of Honduran migrants caravanning north toward the US border to give white people nightmares and get Donald Trump re-elected. Instead, the border was entirely empty.

I walked into the office and it was just me and a surfer dude from the US. I chatted with the Honduran border control agent about Roatan and she stamped me out of Honduras. I shuffled over to the Guatemalan border control agent, who was just the next window over along the same counter. He took my passport and opened it. His eyes got big. He got up from his chair and disappeared into the back room.

Uh-oh.

He came out with another border control agent. Shit. I knew that “Suck it, Guatemala!” passport cover was a bad idea.

I punched the “Spanish-understanding” part of my brain in the face and forced it to translate their conversation. It creaked loudly and dust puffed out as the gears began to mournfully turn.

“Holy shit! Look at this guy’s passport! Look at all these countries!”

“Wow!”

“What is that-”

“Turkmeni-what? Crazy!”

“That’s cool!”

Oh thank God. The first agent smiled with childlike wonder as he added another stamp to my passport. Gracias amigo.

As we cruised through the Guatemalan night, I admired how much better their roads were than the catastrophic roads in Honduras. Right then, my driver subtly reached up by his neck and smoothly slid his seatbelt on and latched it into place.

Oh shit. He hadn’t been wearing it at all for the entire trip, clearly did not normally wear it, but as we accelerated around a slow car and swerved into the oncoming traffic lane, he had obviously decided it was going to be worth the trouble for when we plowed headfirst into an oncoming chicken bus. I unbuckled my seat belt and buckled it again, in case I had plugged it into the ashtray the first time around.

I was however secretly glad he was making good time, because the check-in for my hotel in San Salvador closed at 11pm and after trudging through the endless road delays in Honduras, we were only just barely going to make it.

We slid through Guatemala without incident, and approached the border of El Salvador.

This place was a complete and total madhouse.

Ironically, this is the border one would cross to get away from the United States.

A huge line of cars and colorful buses waited to cross the border. My driver and I left the van parked in line and got into the line of hundreds of people waiting at the border control window, which was outdoors like they also served hot dogs.

Chatting with people in line, we discovered there had been a huge church event in Guatemala and all these people were the church groups returning to El Salvador after it had ended.

Shit. I looked at my phone. Man, we’ve got to get through this quick or I’m going to be sleeping on the sidewalk in San Salvador.

I had a great view of all of this because I was by far the tallest person there. All the Guatemalans were exactly five feet tall. I asked my guide about this the next day in El Salvador and she explained that Guatemala has a much larger native population, and the natives tend to be shorter. Salvadorans are taller and more European because their government killed all the native people there after a peasant uprising in the 1930s. Damn, El Salvador.

As we stood in this endless line for an hour and a half, I watched what was either an absolutely gigantic insect, or a bird covered in cobwebs, flying in a loop around a light bulb hanging from the ceiling. Once we got tantalizingly close to the front of the line, I suddenly realized the guys in front of us in line were each holding a stack of about 100 IDs. Oh my God. These are the bus drivers, and they’re “checking in” everyone from their buses. I think I may live in Guatemala now.

My driver decided this was bullshit of the highest order and politely wedged himself in front of those guys. Go, dude! Once we got to the window, we saw the poor son of a bitch who was in there alone, running all these IDs through a dusty old computer.

After all of this, I laughed when I realized this was just the border to leave Guatemala. There is no border crossing to get into El Salvador. The Guatemala guy literally wrote 2 (as in people) on a blank slip of paper and my driver showed it to a soldier as we crossed into El Salvador. My passport wasn’t checked and I didn’t get a passport stamp. They don’t give a shit. Welcome to El Salvador.

One of the soldiers who checked to make sure our little slip of paper said 2 was in a conundrum. He’d missed the last bus into town for the night. Could we give him a ride? Sure, whatever. He climbed into the van and we dropped him off a few miles up the road.

I looked at my phone. Ai yai yai. There’s no way I’m getting to my hotel by 11pm. Shit. All I can do is call the front desk and plead my case. The only problem was that Salvadorans are well-known for not speaking any English at all. I’d been hitting Duolingo hard leading up to this trip and in every down minute I had as I traveled, and I’d thankfully progressed beyond my “Yo como las manzanas” level of Spanish proficiency from my earlier trip to South America. But this was going to be over a bad cell phone connection, in a noisy van, with someone who I couldn’t see speaking. Also, Salvadorans speak muy rápido. Mierda.

Well, however badly this goes, I suppose it’s still going to be better than sleeping on the sidewalk in one of the purportedly most dangerous cities in the world. I rang up the front desk.

“Buenas noches.”

I began to babble in Spanish, hopefully explaining who I was, that I had a reservation, that I would be late, and asking if they could wait up for me or leave the front door unlocked so I could get in, or else this was going to be the end of my life’s fantastic voyage.

What time? Shit. How do you say “midnight” in Spanish? Would “doce” for 12 work, or do they count in 24-hour time? Shit. Scanning, scanning, scanning. MEDIANOCHE! Yes!

The woman unleashed a salvo of rapid-fire Spanish word salad, of which I caught about three words. One of which was “problema.” Problem. Shit.

I proceeded to explain in rapidly degenerating Spanish that I had nowhere else to stay, and anything else I could think to say in Spanish, including most of the lyrics to “Oye Como Va.” After quite a lot of this, she interrupted me.

“No problema. NO problema.”

AAAAAAAH. Gracias señora! Muchas gracias! I thanked her several times and then I think used the form of goodbye that means “I will never see you again” before hanging up.

My husky driver, listening to all of this no doubt with great amusement, and who I realize in retrospect could have offered to help with translation at any time, asked if we had time to stop for dinner now. Uh, sure, yeah I guess we do.

I expected we were going to stop at some charming roadside food stand or in some grandmother’s kitchen for the most authentic meal of a lifetime. Instead, my driver eagerly wheeled into a McDonalds in Santa Ana. Okay. Lesson One: El Salvador has McDonalds.

Inside the restaurant, I marveled that McDonalds charges the same prices in El Salvador that they do in the US, in spite of the fact that incomes here are drastically lower than they are in the US. That makes McDonalds a fancy night-out meal, a weird inversion of the niche they fill in the US. Everyone working there was amazingly sweet and spoke not a word of English. My driver finally jumped in with help when my inability to translate the Spanish for “Is this for here or to go?” threatened to delay his own apple pie.

The most important thing you need to understand about El Salvador are the pupusas. These are cornmeal flatbreads filled with beans and veggies and spices and they are delicious. They are available every ten feet in El Salvador. At one point our driver zipped past a cop on the road, who I was sure was going to pull us over. I imagined how the interaction would go: He’d give us the ticket, then to soften the blow he would offer to fry us up some pupusas.

Instead he ignored us completely.

If you’re walking down the street in El Salvador and suddenly realize you are hungry, you can just stop right there where the urge hit you, and somebody’s grandma will make you a pupusa on the spot. And I don’t mean they will microwave some frozen pupusa that a factory shat out last year. They will make it from scratch, while you’re standing there. It was surprisingly easy to be vegan in El Salvador because it was obvious what was going into everything, when they were practically pulling the corn out of the ground right in front of you.

And it was all delicious. It’s a strange quirk of the modern world that people in this extremely poor country seem to eat better than we do, largely because they can’t afford our processed chow.

I’d taken the unusual step of hiring a guide and a driver for my time in El Salvador, mostly because I knew that on my own I would accidentally drive into a gang stronghold blaring Juice Newton and this would end the gang conflict forever and American politicians would have no one left to project our fears onto and we’d have to start dealing with our own shit, which is terrifying.

I finished stuffing the last pupusa I could fit into my face and washed it down with an ice cold Horchata. I went to pay the grandma wo-manning the grill for my and my guide’s lunch, and she looked at me like I was insane when I tried to pay with a ten-dollar bill. You can’t make change from a ten? Shit. How much is lunch? A dollar? How can that be possible? It’s for two people and we ate a ton!

Welcome to El Salvador. I had a bitch of a time breaking that same ten-dollar bill over the course of my entire trip.

The best part of hiring a guide, other than not forcing the spiritual reckoning of the American people, was that Natalia knew where all the good food was. Fried yucca with cocoa nut butter hot chocolate. Plantain empanadas. We pulled over on a mountain road at one point and a woman with a little stand took our choice of fresh fruit and ran it through a gauntlet of hot sauce, salt and sugar and shook it up in a little plastic bag before handing it to us. This was an incredible snack. I thought I’d picked an orange but my guide and driver both laughed for five minutes when I called it a naranja, so who knows what the hell it was. It was delicious.

We were driving through dense San Salvador traffic one day when I mentioned that I was thirsty. Our driver immediately stopped the car and gestured to a dude by the side of the road who was whacking coconuts with a machete. He quickly produced a baggie of preposterously fresh coconut water interspersed with hunks of coconut meat. It was goddamned refreshing.

El Salvador has one solution for all of your take-out container, cup and straw needs: a plastic baggie. Everything looked like you were buying a goldfish. I quickly learned the local skill of poking a small hole in the bag and sucking out the contents without wearing the majority of it.

Natalia and I ducked into a pastry shop in downtown San Salvador and asked the grandmother at the counter which of the pastries were vegan. She looked at me and said “Tienes hermosos ojos.” I was trying to figure out which pastry she was talking about when I suddenly realized she’d told me I have beautiful eyes. Dammit El Salvador, you’re trying to get me to move here!

The more amazingly sweet people I met, the more difficult it was to imagine murderous gangs coming out of this place. After a bit of research, I figured out why: The notorious MS and 18 gangs in El Salvador that everyone is so terrified about invading America are from… Los Angeles. Jesus. Self-awareness may not be our strong suit.

But fear not, everyone will be happy to know that my impromptu street performance of “Beat It” convinced all the gang members of 18 and MS to lay down their arms and reconsider their ganging ways, so struck were they by the sheer auto-erotic frenzy of Michael Jackson’s 1982 hit. So, you know, you’re welcome for that and stuff.

My most redeeming trait in the eyes of the Salvadorans was my deep and abiding love for and fascination with their chicken buses. These truly put the buses in Honduras to shame. Nearly every bus was deeply Jesus-themed, as if it was all a huge contest to have the most Jesusy bus in the land. Probably not surprising in a country named after the guy.

Other buses were similarly dedicated to hot ladies. Many were adorned with truly inexplicable Apple logos.

The most danger I encountered in El Salvador was almost getting run over more than once trying to get photos of all the buses.

The buses were not the only hilarious traffic oddities in El Salvador. I was fascinated by the trucks that had a rudimentary pipe frame in the bed that allowed approximately 400 people to stand in the back as the truck thundered down the freeway. It was a lot like the truck I had ridden in the back of in Bolivia, only involving a number of people that suggested this was a stunt on Jackass. I don’t know if this is considered sub-bus transportation or if it’s a step up from the bus because you get plenty of relatively fresh air, but it was startling whenever one of these trucks bounced by.

The other oddity I loved were the ancient cars you’d see on the roads. I don’t mean classic cars, I mean cars that were shitty when they were brand new. We passed a 1979 Datsun that my mom used to drive when I was a kid. I mean, I think this was the actual car. It took me a moment to figure out what was going on. The best I could figure was that anti-smog laws in the US make it too expensive to keep an ancient shitbox like this registered, eventually it’s cheaper just to get a newer car. So these cars fall out of circulation in the US and end up in Central America, like our old school buses.

I looked at the bus driving ahead of us, which was belching out deep black smoke that could only be adequately explained by some part of the bus actually being on fire. Yeah. I don’t think El Salvador has those same anti-smog laws.

Sometimes traffic would stop inexplicably and I’d realize it was because two bus or van drivers had stopped to exchange money, window to window. This was also inexplicable.

El Salvador is a land of volcanoes and earthquakes. Possibly not the most stable twofer a country has ever scored.

We were a quarter of the way up the Santa Ana volcano when my guide wheezed “Leave me, I’ll see you at the top!” and I kicked it up a gear, weaving my way through the dense throng of Salvadorans hiking up the mountain side.

Normally I would be disappointed to not have more solitude on a hike like this, but I quite enjoyed hiking with all the locals, listening to what I could make out from their conversations and giving them a friendly greeting as I passed, when they’d suddenly swear in Spanish and fall out as they realized the mountain keeps going up.

I was the only tourist I saw all day, so people frequently wanted to ask where I was from and express their shock that I was traveling by myself. Virtually everyone I met had family living in America, so they were interested in hearing more about where I lived. These conversations frequently eclipsed the limits of my Spanish, but I lucked out in that a large number of the people hiking that day were students from a language school and their English was excelente.

As we climbed up, Cerro Verde off in the distance ducked in and out of the cloud cover mysteriously.

Far down in the valley below us, the music from a church service echoed across the vast distances and serenaded us eerily in our climb.

We rose above the tree line and the land became rocky and increasingly alien. A few spots offered rough shortcuts bypassing the trail’s zigzagging switchbacks, most of which were shortcuts in distance but not in time, as wrenching yourself up sharp lava rocks is very slow going.

Everyone I met and talked to on the way up was uniformly wonderful. The people all seemed to have a childlike innocence to them that was completely charming.

Reaching the top, the barren rock rolled over the rim and down into the crater. Surreal colors swirled through the rock face as it cascaded down to a steaming crater lake at the bottom of the caldera. The green water of the lake bubbled, as steam curled and drifted like a ghost across the surface.

As I was wandering around the rim, taking in the lake from different angles, a young Salvadoran with a camera stopped me and interviewed me for his YouTube show. So apparently I’m somewhere on YouTube saying not very interesting things about El Salvador.

Eventually my guide Natalia made her way to the top.

“Are you enjoying the view, Sean? Maybe you could stand not so close to the edge?”

Oh Natalia, you card.

On the hike back down the mountain, I stopped and climbed a lookout tower, taking in the incredible view of the entire region.

While we were hiking back down, a man fell and broke his leg. Further down the mountain we crossed paths with the medics carting a stretcher up the mountainside so they could carry the man alllllll the way back down the trail.

Throughout the trip, Natalia and our driver were helping me with my Spanish as I helped them with their English. They both found the word “stretcher” to be completely amusing.

Natalia had done this hike several times over the years, so I asked if she ever saw any animals.

“Just beards.”

“Huh?”

“Beards.”

Natalia had just corrected my confusion of the words “cómoda” and “comida” (best not to confuse a chamber pot and a meal) so I felt comfortable pointing out that this is totally not an animal.

“That’s the hair on a man’s face.”

Eventually we worked out that she meant birds. And I suddenly realized that the way we actually pronounce birds (“burds”) makes no sense at all. Ah, English.

Being a mountain enthusiast, I dragged my guide to El Boquerón next, another huge volcano. I’m told the name means “Big Mouth,” even though I think “boquerón” is Spanish for anchovy, but very little in the world should pivot on my understanding of Spanish. El Boquerón is a much more developed tourist site due to its proximity to San Salvador, so this was less of a challenging hike and more of a stroll through tons of food stands and Salvadorans saying “Holy shit, a white guy!” like that wasn’t the first phrase I learned in Spanish.

The caldera of El Boquerón was dry, but your disappointment could be quickly assuaged by the woman cooking pupusas on the very edge of the rim.

The largest volcano I got to visit was Ilopango, which is filled with the second largest lake in El Salvador. Before I even knew what was happening we were motoring around the beautiful crater lake in a little boat.

San Salvador is the capital and largest city in El Salvador. Of the few tourists who do come to El Salvador, many avoid San Salvador entirely due to the gang issues and their desire to hang in some of the chill colonial villages out in the countryside. Which is fine, but I feel like I would have really missed out if I had done the same. I found the city and the history there fascinating.

Natalia took me on a quick stroll through the city’s street bazaar, where most of the non-wealthy Salvadorans do the majority of their shopping. Of course I found the copious bullshit on sale completely fascinating, even if I could only get photos of half of it due to our rapid walking pace.

My worst photo lapse was in being too slow to get a photo of the pair of panties on display that had “I Love French Kissing” embroidered on their crotch. The clothing in general had a similar theme, which I found hilarious for such a religious country.

Salvadorans also love shoes. Like, more than you love your mom. I have never seen so many shoes in my life.

They’re also fairly fond of Christmas.

Me being me, I was mostly fascinated by the bizarre toys. I couldn’t get enough of this cracked-out Buzz Lightyear. Buzzed Lightyear?

Many of the toysOH MY GOD IT’S THE BEAR GIRL FROM TURKMENISTAN

I backed away slowly, maintaining eye contact until I was safely around the corner. Seeing as how she has now followed me through three wildly diverse countries separated by thousands of miles, I fully expect to see her in my rearview mirror the next time I get in my car. I’m on to you, bear girl who is now somehow much larger than the bear.

We walked past this improbably patriotic store, which turned out to sell massively discounted clothing from the US. So this is where the stuff that doesn’t sell in our stores ends up. It was weird to think of El Salvador getting our hand-me-downs, like our little brother of a country.

San Salvador’s greatest riches, unsurprisingly, are its churches. My favorite by far was Iglesia El Rosario, a beautiful and strikingly modern church built in 1971. The church is shaped a bit like a curved concrete bunker, with two phalanxes of East-West facing stained glass windows that capture the sunrise and sunset and stream them magnificently into the church. This is arguably the coolest thing in El Salvador.

One entire wall of the church is a huge stained glass eye of God, making sure you didn’t put any coupons into the collection plate.

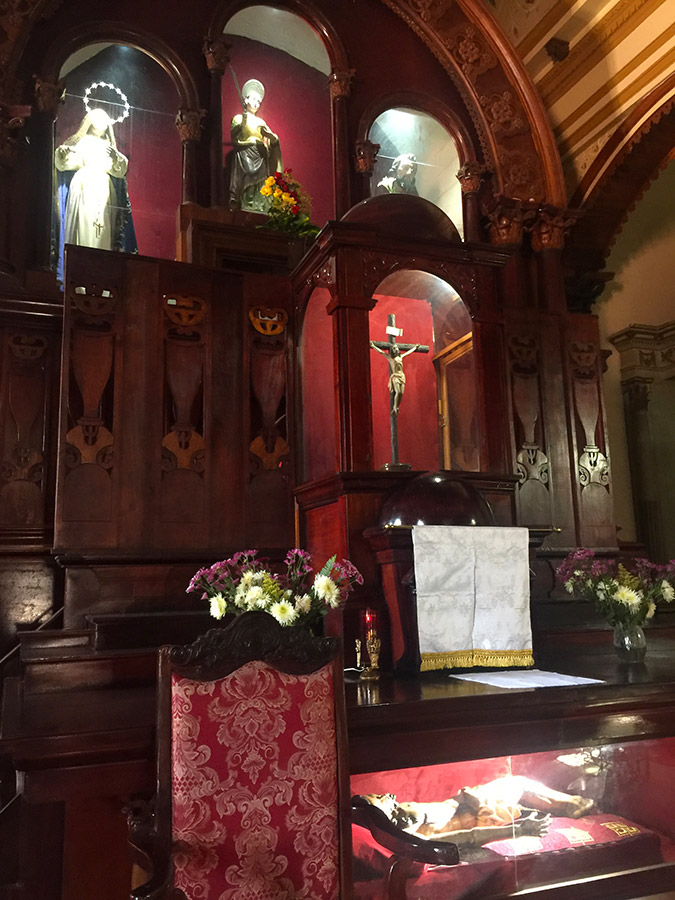

The runner-up best church in San Salvador is the more-traditional Basilica Sagrado Corazon de Jesus.

Inside, the roof is held up by a fascinating lattice of ironworks that looks like the hull of a Viking ship.

Walking around inside the church, I met a friendly Salvadoran man who was happy to meet an American. He’d had to leave his wife and kids behind in America once his unauthorized entry had been discovered, after years of living and working in the US. And now he was waiting out the years until he could legally return. This kind of story is shockingly common in El Salvador.

My guide hadn’t seen her dad at all in the 15 years he’d been working in the US and sending money back to support the family. This being a huge chunk of her life, it was like he didn’t exist. Family ties are bizarrely distorted by the fact that even a shitty job in America is a huge income for the family left behind in El Salvador. Virtually all of the MS and 18 gang members in El Salvador grew up without parents, their mothers leaving them behind because the crossing into the US was too hazardous to take a baby. They were raised in El Salvador by an aunt or other family member the mother was sending money back to, and the gangs eventually ended up becoming their family of choice.

Virtually everyone I talked to in El Salvador was playing one of the roles in a story similar to this.

The father in the church and I chatted. He was traveling through Central America while waiting out his exile from the US. Very few Salvadorans I talked to had been to any other countries, the few who had left El Salvador had just been to Guatemala. People had passports full of stamps back and forth from Guatemala to El Salvador, nothing else. So it was with a bittersweet note that the father was enjoying seeing more of the region. He was eager to do some hiking and I gave him some tips about the volcanoes I’d hiked so far on the trip.

The most emotional church visit however, was to San Salvador Cathedral. Not for the church itself, which was fine, but similar to others I’d been in that day. But in the basement, there is the tomb of Oscar Romero.

Archbishop Oscar Romero is El Salvador’s national hero, a canonized Catholic priest who spoke out for the poor and against social injustice, which brought him into conflict with the Salvadoran government.

In 1979 a coup deposed the president and led to the Salvadoran Civil War, which lasted through 1992 and led to 75,000 deaths, most of them civilians. The causes for the war reached back to the 1800s, when wealth from coffee grown in El Salvador created massive income inequality. In 1932, the peasants and indigenous people organized into a socialist party seeking greater equality, and the government responded by killing all 30,000 of them.

Similar tensions sparked the civil war in 1980. The government organized death squads to wipe out entire villages thought to be in support of the socialist guerilla groups. The US supported the El Salvadoran government, supplying over $1 billion in aid through the Carter and Reagan administrations and appointing US military staff to lead the Salvadoran armed forces.

Romero sided with the peasants, calling on the death squad soldiers to lay down their arms and stop killing civilians during a widely broadcast sermon in 1980. The next day, Romero was shot in the heart while delivering his sermon at a hospital chapel. The gunman was believed to have been hired by a Major in the Salvadoran army who had been responsible for setting up the death squads.

Romero’s tomb in the basement crypt of the church is a striking design, featuring a reclining Romero flanked on all four corners by four ghostly female figures. A red jewel on his chest marks the spot where the bullet entered.

Locals frequently come to the tomb to pray to Romero for intercession on behalf of themselves or their loved ones. Romero became a saint in 2018 after a man whose wife was in a coma prayed to Romero, and the wife recovered. While we were in the crypt, a Salvadoran family was at the tomb, praying emotionally and at great length to Romero for help with their son who was sick.

This was, of course, completely devastating, but also inspiring to see both their love and their faith on display.

Knowing a bit about the history of the civil war made wandering around San Salvador fascinating. Government snipers had fired upon the men carrying Romero’s body into this very church, and 50 mourners were killed when the army attacked the funeral itself.

Every public square I walked through had hosted battles, tanks rolling down these same streets. Natalia told me stories about relatives of hers being on opposite sides of the war, which is both horrible and fascinating to imagine.

Near San Salvador we took in the Mayan ruins of Tazumal.

These were fun to see but a bit underwhelming compared to Copan in Honduras. The main problem was that El Salvador’s frequent earthquakes had necessitated coating the stepped pyramid in concrete to keep it from dissolving into a bowl of Grape Nuts. This is completely understandable but does make the entire site feel like a recently-constructed mini golf course, without the mini golf.

I did quite enjoy the beautiful trees and unexpected cacti laced through with spider webs ringing the perimeter of the ruins.

Inside the nearby museum, Natalia told me the story of this Mayan leader, who wore the skins of his enemies like Mayan Buffalo Bill. My understanding is that he also had a hand he could swap out for a sword or a machine gun.

That’s… Okay yeah that’s horrifying. This other guy won every awesome hair contest that was ever held:

The furthest we ventured outside of the capital city was to drive northeast to Suchitoto, a well-maintained Spanish colonial village from the 1800s that was far enough away from the action to emerge intact after the Salvadoran Civil War. This is basically where people in the know go when they go to El Salvador.

The jewel of Suchitoto is the parish church of Santa Lucia in the center of the town.

Inside, I was dazzled by the beautiful woodwork in the pillars and arches running alongside the pews spanning the entire length of this long, narrow church. At the opposite end, the altar is backed by a huge cabinet featuring wooden statues of Jesus, Mary and Joseph behind glass. Full disclosure and with no disrespect, I fully expected these figures to suddenly start moving and to sing Happy Birthday to You at any moment. I was disappointed that I did not appear to be there at the right time of day for this to happen. And also that there was no skee-ball.

The side walls of the church featured several smaller cabinets featuring even more statues. I’d never seen anything quite like these, as all the statues were wearing clothing and wigs, like marionettes or ventriloquist dummies. Natalia explained this was because they are carried in parades on holy days, which would be a real test of faith with a heavy marble statue.

Beyond the church, I found Suchitoto a little underwhelming, though it would be a nice place to have a very relaxing hang-out vacation and it did give me the opportunity to sweat all over a postcard and mail it back to the States. Down the hill from the town is Lake Suchitlan, which features a tiny island in the middle with a zip line running out to it. Birds perched on the rather flat zip line, leaving me to wonder what your options would be if you didn’t have enough momentum and got stuck in the middle.

On the drive back to the city, I took many very, very blurry photos of the beautiful artwork on the sides of the buildings.

Getting to the San Salvador airport (which is nowhere even remotely near San Salvador) for my flight back home was complicated by the fact that I didn’t know how to say “the day after tomorrow” in Spanish. In retrospect I realize I could have pulled up the DVD cover for the movie of the same name on my phone, but with my luck it was probably called American Shitstorm when it was released in El Salvador.

The intimidating woman running the very small “hotel” where I was staying didn’t speak a word of English, which made arranging a driver difficult. Ultimately I just decided to wait another day before asking her, since I did know how to say “tomorrow.”

When I relayed this story to Natalia and my driver the next day, they laughed for several minutes. And then arranged a ride for me to the airport.

Top 10 Things You Probably Shouldn’t Do at the Start of a 13-Hour Travel Day

1-10. Eat a whole bag of prunes.

Going through security at Monseñor Óscar Arnulfo Romero International Airport, the woman running the scanner pulled out my bag and confiscated the fork and “knife” from my bamboo travel silverware set, as a threat to the survival of the flight crew. This was hilarious both because I’ve traveled all over the world with this same set, and because neither of these items could puncture the skin on a bowl of yogurt. Whatevs, El Salvador.

Deeper into the airport there was a second security check. At this one the dude confiscated my mosquito spray with a “Tsk Tsk Tsk” gesture. Keeping in mind that I had several unlabeled liquids in my bathroom kit that could have been absolutely anything from jet fuel to the virus from 12 Monkeys. Clearly my mistake was in having my pump-spray Picaridin clearly labeled.

So this is El Salvador’s big airport. It smelled a bit like jet fuel and burnt corn. I like to go home with a few notes of the local currency from whatever country I’m visiting, which was complicated by El Salvador’s use of US dollars since 2001. Previous to that they’d had a currency called colones, which I was completely unsuccessful in finding anywhere, including every single souvenir shop at the airport, though I was successful in finding a lot of Salvadorans who will look at you like you’re totally insane when you ask for colones. I was probably pronouncing it wrong and asking for a colonic.

I fished a Sacagawea dollar coin out of my pocket. Oh well, this will have to do. Nobody uses these in the US, but they’re extremely popular in El Salvador, much like our unsold shoes.

OK, I’ll just get some pupusas to go. I proceeded to get shut down at every restaurant in the airport for requesting pupusas without any queso, receiving another plentiful bounty of “No cheese? Are you crazy?” looks from incredulous Salvadorans.

Hmm. My stomach grumbled. Agua? Water at the airport was $7 a bottle, which is normal for an airport but insane compared to the cost of everything else in El Salvador. Hmm. I’ve got a long flight and then a layover in Miami, I’m going to need water. The last time I didn’t buy a bottle of water I ended up asking a Polish flight attendant to refill the Dixie cup she gave me 17 times and she thought I was completely insane.

I broke down and bought a bottle, and walked the 20 feet to my gate.

There was another bag scan at the gate, and they immediately confiscated my unopened bottle of water. Are you crazy? You can’t bring water into the gate! J.F.C. El Salvador. Why do you sell huge bottles of water right next to the gate when you can’t bring them into the gate? I was grateful that the bag scanner girl didn’t speak English when I inadvertently swore out loud. I took my bag back out of the gate, into the hallway, and looked left and right. There was nowhere to sit down. I sat on the floor and chugged the entire massive bottle of water.

Nice try, El Salvador. I still love you. And will continue to do so assuming I don’t piss myself on this flight.